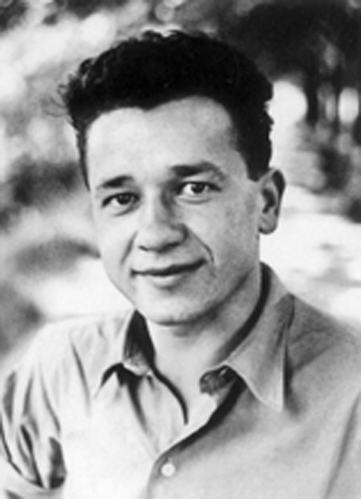

By Charles Fishman: Louis Daniel Brodsky

Louis Daniel Brodsky is the publisher of

Time Being Books in St. Louis and a gifted and driven poet who produces volumes of his own poetry with astonishing regularity. I have read at least six collections of his poetry and recently tore through

Rabbi Auschwitz, released earlier this month, and

The Swastika Clock, which is scheduled for 2011 publication. Many of the poems in these two outstanding collections are marked by originality and power, and I have read them many times. I should also mention that “L.D.” brought out my 2006 collection,

Chopin’s Piano, and the second (and extensively revised) edition of

Blood to Remember: American Poets on the Holocaust (2007). It should be no secret, then, that I consider his work, both as a small press publisher and as a poet, exceptional and believe it merits our close attention. It was partly for this reason that I decided to conduct an interview with him, but it is also true that I wanted to learn why this amazingly productive literary man has written so many poems about the Holocaust and why he often uses wholly imagined and “composite characters,” as he calls them, when writing poems that relate to the Shoah.

The interview was conducted during January and February 2010. This is the first of two installments; the second will be posted later this month.

CF: Did you begin to write poetry because you wanted to express your feelings about living as a Jew in the aftermath of the Holocaust?

LDB: No. In fact, all through high school, back in the fifties, and beyond the mid-sixties, spanning my graduate-school years, when I began my writing career, I wasn't cognizant of the Holocaust. No one spoke of it, in my teenage years especially. It was as though the very word "Holocaust" was taboo, a stigma, a subject one didn't mention anymore than Orthodox Jews spoke the word "God." I had no training in Holocaust literature. There wasn't very much of it, back then. Since no one in my family was affected by the Holocaust, I didn't even have the secondhand perspective that heritage provides — stories handed down, whispered with lamentation. I was passionately interested in Spanish and English and American literature. In the month before I graduated Yale, in 1963, I wrote my first two poems and sensed, then, if inchoately, that I wanted to be a writer who would write about everything, spend the rest of my life composing poems that would connect me to the world beyond myself, worlds waiting to be, waiting for me to discover and expose them, breathe life into them. One such world would be Europe, Nazi Germany, 1933-1945.

CF: It’s a little surprising that you are not a Holocaust survivor or a relative of a survivor, yet you have probably written more poems about the Holocaust than any other American poet. In a recent email, you stated the following: "I've written, since 1967, 322 of them. Would that I had written not one. But such is not the terribly tormented truth." What is it that drives you to continue wrestling with the Shoah in your poetry?

LDB: What it is that drives me is a lingering self-consciousness that began in fifth grade, when my parents sent me to what was considered the finest private boys' school in the city, St. Louis Country Day School, whose enrollment was overwhelmingly white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant, a school that had an unwritten quota of 10 percent Jews, 5 percent Catholics, no blacks. I felt very excluded from social events, felt extremely uncomfortable attending chapel services, every morning, before class. I was required to sing hymns to Jesus Christ and listen to theological speakers. All of it reminded me that my fellow students went to church, every Sunday. Over the eight years I spent there, I always felt ostracized. I was never invited to the gentile parties and dances, couldn't take spring-break trips to Fort Lauderdale, because Jews were off limits there — another of those unwritten quotas. I always sensed that I was an outsider, a pariah, decidedly second-class, no matter my distinguished athletic and scholastic accomplishments.

One incident, in particular, from that time, yet lingers as a painful reminder of just how estranged I felt from Country Day's class of '59. During the final months of my senior year, I and three of my classmates learned that we'd been accepted into Yale's class of 1963. Having never been away from home, by myself, other than for my annual eight weeks at summer camp, I was extremely relieved when the four of us decided to sign up to room together. Toward the end of the summer, just weeks prior to our leaving for New Haven, I was casually informed, by one of the three, that a fourth classmate, whose wealthy father had bought him in to Yale, was going to room with them, instead. It was apparent to me that they wanted to maintain their WASP integrity. Suddenly, I found myself not only persona non grata but cast adrift. At that point, I was more terrified than angry. While flying to New York, then taking the train to New Haven, I'd never felt lonelier.

But something happened, then. My fear transformed into anger, anger to outrage, outrage to an overwhelming sense of purpose. I needed to punish those fellows, and the only way I had for doing so was to try to best them in athletics and scholastics, to which end I devoted myself, with almost maniacal focus. That year, I was first-string left fullback on the freshman soccer team and earned my numerals. Also, I stroked the freshman heavyweight crew. At season's end, I was given the Coach's Cup, for being the best oarsman, and, again, got my numerals. Two of those four classmates, on the other hand, who tried out for the freshman football team (they were outstanding players at Country Day — better than I, by far), ended up being cut. All four of them had very inferior grade-point averages, that year, but I made the dean's list, both semesters.

What I learned, that first year, was that the bigotry those four exhibited went far beyond them. Yale was nothing other than a more sophisticated extension of St. Louis Country Day School, an even more elitist confederation of entitled prep-school legacies and jocks. Because Yale was larger, less personal, the anti-Semitism didn't seem as noticeable, flagrant. Yet it was a given that I would never be tapped for Skull & Bones.

In hindsight, what I can so clearly see is that for my parents to be able to send their firstborn child, their oldest son, to two such prestigious schools was the overt sign that they had arrived, no matter that both schools were Protestant bastions of blue-blood, old-money, patrician society.

After all, my great-grandfather, Daniel Brodsky, had begun, in the late 1870s, hawking hand-me-downs, yet succeeded, by the end of his life, in acquiring some modest real estate, and seeing to it that my grandfather, my namesake, Louis Daniel, had enough wherewithal to start Nelson Trouser Co., a modest enterprise with a decidedly non-Jewish-sounding name, so that, in his time, his son, my father, Saul, could do his apprenticeship before his father suffered bankruptcy, two years before the Great Depression, only to have my dad resurrect the company as Biltwell Company Manufacturers, a maker of men's jodhpurs and dress slacks, which he'd bring to the pinnacle of success, in the post-World War II years. By the mid-fifties, my father would become a self-made millionaire, albeit with too many memories of having been discriminated against repeatedly, told "Jews aren't welcome here," when he'd ply the highways, with his sample garments stuffed into bulging black cases.

I suppose the humiliations from those early days of working with his father (and, later, driving a five-state sales circuit and nurturing my broken grandfather, by making a place for him, in his new business, until the day, in 1937, when Louis Daniel — Lou — died of a heart attack, out on the sidewalk, smoking his signature meerschaum pipe, in front of my dad's office, at 1128 Washington Avenue) were why Saul would never share, with me, any of his deeply suppressed memories of his youth, almost never disclose why he'd straightened his curly hair, why, in his affluent years, he'd personally hand out Christmas gifts to the entire St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, with each officer coming into his '50s-modern headquarters, still at 1128 Washington Avenue, one by one, to choose between a ham or a turkey, a scene that I, at six, eight, ten, could only marvel at; after all, that was my three-piece-suited dad those fully uniformed, black-booted, square-chinned motorcycle, horse, and street cops thanked profusely. Being extremely taciturn with me, he never elaborated on all the Jew-hating entrepreneurs in the small towns of the Illinois prairie, the Jew-baiting backwashes of Arkansas, Tennessee, and northern Mississippi, the plains ranging just beyond Missouri, into Kansas and Oklahoma, all of whom dismissed him before he could get two steps past their polished-brass front-door step plate.

Now, I certainly see it — why he never would tell me about his past. He was still smarting, still ashamed, still scarred despite his ultimate wealth.

In fact, after all these years, I vividly remember a scene in which my father and I, in early 1980, were sitting in the breakfast room of his house. I was so excited to show him the galley proofs of two of my poems, "Résumé of a Scrapegoat" and "Between Connections," which were scheduled to appear in the December issue of the Southern Review. My pride was twofold: first, that my work was appearing in such a prestigious literary magazine; second, that the magazine's editor, Lewis P. Simpson, had responded with such enthusiasm to the poems' subject matter — my Jewish traveling salesman, Willy Sypher, peddling his garments through the Midwest and the Mid-South, having to confront the bigotry of small-town U.S.A. When I handed the proofs to my father and watched his eyes skitter back and forth, over the pages, I was anticipating his validation. Instead, he looked up, bewildered, scowling, and remonstrated, "You're not going to publish these, are you?" My heart sank. Suddenly, it came rushing up to me: he was shocked, appalled, that I would expose my Judaism to public scrutiny, make myself vulnerable, open to ridicule, castigation — this when he was in his financially-secure early seventies and had no need to worry about exposing himself as a Jew and, thus, risking his career. I still recall becoming defensive, rebuking him for his still feeling the need to hide his identity. I slunk out of his house, disappointed, dejected, humiliated.

Yet his reaction should probably not have come as such a surprise to me, since it was, in fact, commensurate with the protective behavior he'd exhibited toward me throughout my youth. His impulse had always been to spare me the corrosive anti-Semitism that had dogged him from his teens well into his fifties, little realizing that his newly established fortune would make it all the easier for me to discover the true nature of racial discrimination, when he thrust me right into the lion's den — a ten-year-old kid encountering, for the first time, in Class 8 (fifth grade), at St. Louis Country Day School, the inculcated disdain of gentiles threatened by the gradual incursion of nouveau-riche Jews into their long-established social and mercantile corridors.

By the time I entered the graduate English program at Washington University, in St. Louis, in 1963, I'd developed a justified sensitivity to intolerance, bigotry, hypocrisy of the religious, more than the political, variety. But not until 1967 did I write my very first Holocaust poem, to my great surprise: "Valediction Forbidding Despair." It erupted from my guts more than from my intellect, from a nauseating, appalling sense of disgust, on having finished reading Jean-François Steiner's book Treblinka, which was prepublished, in English, translated from the French, in two successive issues of Look magazine and was truly my first exposure to the ghastly, atrocious events of the Shoah.

Valediction Forbidding DespairThis summer is Treblinka;

Its regimental months

Are maws that caress us

In bloodless custody.

Victims, like crickets

Scratching dryness from limbs,

Chant hymns from lips

Which shape the air

With unfinished kisses.

Musicians and carpenters

Guard darker silences

Of those who crowd naked

In boxcars and chambers

Where perfumed night descends.

Memories race down chutes

To steaming graves

Obsequious few ply with balm.

Yet

Minds are excused from spirit.

The end obliterates nothing

But flesh

And the temporary wish

To rest.

This poem shocked and horrified me. It also released a terrible, gnawing sense of shame and guilt. And though I couldn't have known it then, it held the seeds of what would blossom into a very, very ugly and poisonous plant. I didn't know I had such angst in me, such rage, such hatred toward what and who it was I didn't even understand at that point. Nor did I know that I wouldn't write another Holocaust poem until 1974. All I knew was that I couldn't believe people could possibly treat other people with such brutality, such merciless murderousness.

By then, I had decided against teaching, as a profession, and was living with my wife and first child, in a small mid-Missouri town that seemed to boast one Jew: me. In the end of July 1974, on a trip I made to a factory that was part of Biltwell Co., Inc. (my father's company, for which I now worked), as I focused on all the women at their sewing machines, I began to imagine my family heritage, those ragmen from a past my father never talked to me about, a past that played itself out in Ukraine, from which my great-grandfather, Daniel, and great-grandmother, Anne, emigrated, in 1875, before arriving in New York, then St. Louis, to begin life anew, as less-than-modest merchants who bought, for pennies, garments needing to be repaired and washed, which they did, before putting them up for resale, for nickels, dimes, quarters, in an outdoor stall. That night, I wrote a breakthrough poem, one that I couldn't know would open up a whole vista into my heritage, albeit one I'd mainly have to invent out of tatters and strands and threads of my imagination: "Breaking Stallions."

Breaking StallionsI ride naked

Atop the sweaty genome of chromosomes

Bucking dizzily in a corral

Where generations of my forebears

Have been thrown

And broken their spines in the dust.

Ancient eyes are on my performance,

As I try to break the leaping creature

Trapped in its frenzied fear

Of not being able to unseat me.

We hang as one on the hot air,

Each obsessed with maintaining stability

And prevailing in the face of a history

Racially oppressed for ages.

Damn the whiskered ragmen

Who've tracked me to this time!

Goddamn them for reminding me

Of the proud and threadbare tailors

Who rose from crude peasant stock

Ravaged in the Steppes beyond Kiev!

Why, for so long, have I eluded

Their hereditary nets and thrived

In an academic nether world,

Only to be dragged back

And forced into a raw saddle

Atop survival's frothing wild stallion?

I reel in a drunken paraplegia.

My feet rip loose from the stirrups.

Caught in the vortex of old dust

Blocking my nostrils and throat,

The stench of my flowing blood

And the shame locked in my brain

Can't mistake the truth of my defeat

Or negotiate another compromise

With genes that have permanently hurled me

Into a factory of trouser-making machines.

This poem had such a transformational effect on me because it made me aware of my ancestry, something I hadn't ever been exposed to, growing up.

A month before I composed "Breaking Stallions," I experienced an anomaly, in the form of a poem called "Panning for Gold." Most likely mentally cued to such atrocities, from having read Steiner's book, I must have read an article about the gold fillings Nazis extracted from Jewish corpses and found it so grotesque that I had no choice but to write about it. That this poem virtually coincided with "Breaking Stallions" wasn't serendipitous.

Panning for GoldIn among the ash heaps,

Prospectors haggle over the gold teeth.

Each keeps a daily assay

Of nuggets he retrieves: caps and inlays

Once securely positioned

In upper-class European circles

Of smartly dressed patronesses of the arts,

Sophisticated financiers, politicians,

Concert pianists, and rabbis

Named Jacobs, Weinstein, Prinzmetal,

Schwartzkopf, Kalish, Abrams,

Rabinovitz, and Glazer.

Now, forty-three years later,

Bounty hunters shake their sieves

At Auschwitz, Bełżec, Chełmno;

Their death rattles shatter the silence

With white noise so loud

It would wake the dead were any still alive.

As the teeth are brought to auction,

Bidders grow restless; they get frenzied,

Aggressive, hostile, genocidal.

Their ear-to-ear sneers

Expose myriad gold-filled cavities,

Intricate bridges and plates.

Dealers trip over numb tongues,

Bite lips to bleeding,

Quixotically jumping their own bids

To insure they secure the lot.

After all, they have clients worldwide

Whose collections are complete . . .

Except for the extremely precious teeth.

Something about this poem, not only the gruesome idea of auctioning the teeth but the grisly irony of the last three lines, brought my intellect to its knees.

A month later, I wrote a poem called "Grandfather," which incorporated both my family heritage and the Holocaust.

GrandfatherDamn it. Goddamnit.

That dear man is dying of cancer.

He refuses to eat or be fed intravenously,

Desires to die at home in bed, desires

To die,

and here I am lamenting his loss

As though I know him for the close friend

I wish he had become

rather than the shadow

Of a vague acquaintanceship we made

On occasional High Holy Days and Friday nights.

We're the keepers of their ashes,

those gone souls

Devastated by wars among their leaders,

People designated by scrolls on their doorposts

And frontlets between their frightened eyes

to be spared famines and blights on Pharaoh

For the cyanide.

We're their keepers

In spirit, self-appointed, properly anointed

With a seminal heritage we share

through ancient marriages.

Our births, though fifty-five years apart,

Are marked by a tribal family name

Sealed in common ceremony.

That dying man,

With whom I tried to reason only once

Concerning the meaning of a living religion,

Is reason enough for my lamentation:

His loss is mine;

his departing shadow

Will deprive me of that constant reminder

That all those gone people

rely on me

To substantiate the decency of their existence.

That was in August 1974. It would take me another sixteen months before the Holocaust poem "Dreamscape with Three Crows" would be written. I must have needed that hiatus, interlude, moratorium, to allow my mind to assimilate these two deep, vast veins, which would begin to manifest themselves in obsessions that, to this day, thirty-five years later, continue to trouble and anger and sadden me enough, beg me, exhort me, force me, to give them life, in the form of Holocaust poems.

When I reread "Grandfather," today, I realize that what's inherent in this poem from so long ago is the core of that which still motivates me to write Holocaust poems. I feel that I'm the keeper of my people's ashes, a keeper in spirit, a self-appointed scribe, sofer, and that it's my responsibility, my mandate, my mission never to lose touch with them. I'm best able to do so when I'm deeply immersed in the Shoah, through poetry.

CF: Was

Falling from Heaven: Holocaust Poems by a Jew and a Gentile (Time Being Books, 1990), the collection of poems you collaborated on with William Heyen, the first book of poems on the Holocaust that you published?

LDB: No. My first book was

The Thorough Earth (Timeless Press, 1989), and it came about as follows.

In June 1976, I composed another poem, "Résumé of a Scrapegoat," that would significantly jolt my self-awareness. It was a full-fledged portrayal of me as a ragman/road peddler and the victim of age-old Jewish oppression. The nameless character is the creative, imaginative epitome, manifestation of what I'd experienced in my very narrow and highly insular life, to that point. The poem captures the essence of the self-conscious me in disguise. I was that scrapegoat — the lowliest of the goats, the one who "scrapes" the bottom of the barrel, the one who was beginning to take the shape of the downtrodden traveling salesman I'd soon name Willy Sypher, who'd become the embodiment of, the synecdoche for, the victims of Pharaohs, Nebuchadnezzars, Herods, Hitlers, the sad, lonely, proud, indefatigable soul I'd eventually immortalize in a book devoted to his daily travails and tribulations, his lifetime of disappointments and small successes, a book of poems very close to my heart,

Peddler on the Road: Days in the Life of Willy Sypher (Time Being Books, 2005). Willy is a Jewish schlepper who represents, for me, not only my great-grandfather and father, not only their forebears from the shtetls of Eastern Europe, not only their tribal sand-dwelling ancestors of the Abramic and Mosaical days in the Biblical Fertile Crescent, Mesopotamia, but me, as well.

Résumé of a ScrapegoatEvery highway I drive,

With station wagon straining to contain goods

Brought up out of steerage,

Is Hester Street,

And I'm the displaced waif

A hundred ancient diasporas left behind

To hawk rags and stitched shit

Made in sweltering lofts and dank basements.

I'm the entremanure of flawed raiment,

Remainders dead as flounder

Stacked flat on shelves

Or hanging in static masses from racks

The lowest class capitalist,

Searching low and lower for newer Laputas

In whose depraved precincts

I might display my thieves' market.

I'm the wide-smiling, gold-filled mouth,

The glistening, beady eye,

The hooknosed, seven-foot shadow

That demonizes Teutonic children's dreams,

The eternal, stereotypical victim

Hanging by my three pawned balls

Outside the emporium with shattered plate glass,

Cluttered with xenophobic bigotries.

I'm the scrapegoat for last season's guilt,

Soiled hopes, dreams with tiny holes,

Spirits returned for overlooked defects,

Mismatched leisure lifestyles,

The robber baron impeding competition

By fixing prices on perfects

I label "Irregular" and flawed garments

I advertise as "Grade A" merchandise.

History's kiss has touched my lips

With the viper's flicking tongue,

Singled me out from the crowd

To toil in dirty gutters and alleys

With cunning and guile, quietly,

By the sweat of my Semitic brow,

While crawling naked on my scaly belly

To avoid being swastikaed by sign crews

Gluing posters, on every available board,

With news of another outlet-store

Or wholesale-chain opening

In a strip mall or shopping center. Amen.

Shit! I'd give my eyetooth

Just to be the solid-gold watch

Tucked neatly in Pierpont Morgan's

Well-stretched Protestant vest pocket,

Instead of a thimble-fingered tailor

Drawing chalk lines and pinning seams

Across the whim of every fat ass

Able to afford his own graded patterns.

Yet history's also nourished me

With fruits from the tree of life eternal.

I've peddled myself from one generation

To the next, a perpetual hand-me-down,

Promoting my own brand of survival

At cut-rate prices, offering my soul,

On a moment's notice, to anyone

Who'd wear robes like those I sewed for Moses.

In October 1982, I read a review of a book, published in England, that piqued me in a very strange way, a volume by Australian writer Thomas Kenneally,

Schindler's Ark. I bought the book and read it in two sleepless nights in that small Missouri town, where, as a father of two children, by then, I was working in Biltwell's Farmington factory. As had been the case with Steiner's

Treblinka, I was stupefied, appalled. I felt personally degraded. I reread the book, a few months later, and in April 1983, I composed "Cracow Now," a poem in which I staked claim to my role as poet-in-residence for my people, a "messenger for the dispossessed."

Cracow NowDefeated, exiled, indefensibly committed,

Those dispensable souls

Relegated to the ghetto in Cracow:

Bankers, Talmudic scholars, grocers, musicians,

Strict, disciplined family men,

Whose reverential Leahs, Rachels, Miriams

Bore, in pride, brilliant children —

Ghosts now, still guiding wheelbarrows,

Filled with pillows and sheets,

From cultured salons, in family estates,

To ventilator shafts, attics,

And dead air-space between rooms

In hovels cluttering memory's tear ducts.

The metamorphosis of three centuries,

Accomplished in months: Jew to lice to typhus.

Then the Madagascar Plan.

In the end, only Hitler's witless tactics

(Matching his storm troops

Against Russia's forces of winter)

Could suspend the Final Solution,

For tribes confined to greenhouses

Producing a variety of Venus's-flytraps so profuse

Neither Linnaeus nor Darwin

Could have classified them:

Auschwitz, Treblinka, Bełżec,

Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibor.

Just writing their bleak syllables chokes me.

Each is a puff of black smoke

Escaping crematory stacks

Punctuating skylines of my verse,

Each a caesura too frequently breathed.

This morning, four decades downwind,

The measures of my sanity dwindle.

I, too, as messenger for the dispossessed,

Wearing a "J" on my brain-band,

Push all my earthly belongings — paltry words —

In a rickety wheelbarrow, across the years,

Toward precarious lodging

In the ghettos of your unsuspecting ears.

Not until May 1986 did I actually group some of what I considered my most powerful Holocaust poems together, in a pamphlet called "Selections from the Ash Keeper's Everlasting Passion Week." The term "ash keeper" had stuck with me, from 1974's poem "Grandfather," in which I determined that my grandfather, whom I didn't really know, and I would be "the keepers of their ashes," those of our agelessly persecuted people. This collection would be the germ for the conception of my first book of Holocaust poems, titled

The Thorough Earth, which was published by Timeless Press, in August 1989.

Regarding this first of my nine completed volumes of poetry about the Holocaust, Lewis P. Simpson wrote:

No achievement in his poetic career exceeds Louis Daniel Brodsky's creation, a Jewish travelling salesman for a Midwestern manufacturer of men's clothing, who, in an earlier version of his life, “sewed and sold to Abraham and Moses.” Juxtaposing a series of poems about Willy's career and a series of poems reflecting on the Nazi Holocaust, Brodsky projects a vision of Jewish history in

The Thorough Earth that includes in its range the comic compulsiveness of Willy's quest for sales and the unspeakable horror of the death camps. No poet at work today has a more vividly ironic sense of history combined with a more passionate regard for the infinite worth of the experience of being alive.

__________________

Louis Daniel Brodsky, born in 1941, has written sixty-four volumes of poetry, including the five-volume

Shadow War: A Poetic Chronicle of September 11 and Beyond.

You Can’t Go Back, Exactly won the Center for Great Lakes Culture's (Michigan State University) 2004 best book of poetry award. He has also authored fourteen volumes of fiction and coauthored eight books on William Faulkner.

The link for Time Being Books is

http://www.timebeingbooks.com/. Louis Daniel Brodsky’s website is

http://www.louisdanielbrodsky.com.

The second part of this interview with Louis Daniel Brodsky will appear on Writing the Holocaust later this month.