Marked: Poems of the Holocaust by Stephen Herz is probably one of the best

poetic introductions to the Holocaust. In language that is clear and

resonant, Herz tells us what we need to know in images and lines that we will

not soon forget.

Here are two poems from the collection ("Morgen Früh" and "Whatever You Can Carry") and several stanzas from "Shot," followed by an interview with Mr. Herz regarding Marked, its genesis and intentions.

POEMS

Do you know how one says never

in camp slang? Morgen früh:

tomorrow morning.

—Primo

Levi

Will you wake on a plank of wood

with six others,

wash your face in your morning coffee,

and go to work in the mud?

Tomorrow morning.

Will you go to the latrine when

they tell you,

or be shot at roll call

because you did it in your pants?

Tomorrow morning.

Tomorrow morning

the boils and pus and lice

will be gone,

the blue tattoo will fade from your wrist,

the green dye will fade from your eyes,

the sweet singed smell

will fade from your nostrils.

Tomorrow morning

they’ll give you back your ovaries,

give you back your children,

give you back your old wool coat

with the yellow star,

and you’ll give them back

the paper cement bag

stuffed under your dress.

Tomorrow morning

you’ll run a comb

through your long black hair,

tie it with a bright red ribbon,

and someone will smile and say:

Good

morning,

Lena.

Tomorrow morning

there’ll be no more ashes

to fill the swamp

to dump in the river

to fertilize the fields. No more ashes

to spread on the paths like gravel

under the boots of the SS.

Tomorrow

morning.

Tomorrow

morning.

Morgen

früh.

Whatever

You

Can

Carry

Twenty-nine storerooms

were

burned

before

the liberation

of Auschwitz.

In the six that remained

they

discovered

348,820

men’s

suits,

836,255

women’s coats, more than seven tons of human hair and even 13,964

carpets.

—Michael

Berenbaum: The World Must Know

“You will work in the factory, work in

the fields, you will be resettled in the East,

bring whatever you can carry.”

So our dresses, shirts, suits, underwear,

bedsheets, featherbeds, pillows,

tablecloths,

towels, we carried.

We carried our hairbrushes, handbrushes,

toothbrushes, shoe daubers, scissors, mirrors,

safety razors. Forks, spoons, knives,

pots, saucepans, tea strainers, potato

peelers, can openers we carried. We carried

umbrellas, sunglasses, soap, toothpaste,

shoe polish. We carried our photographs.

We carried milk powder, talc,

baby food.

We carried our sewing machines. We carried

rugs, medical instruments,

the baby’s pram.

Jewelry we carried,

sewn in our shoes, sewn in our corsets,

hidden in our bodies.

We carried loaves of bread, bottles of wine,

schnapps, cocoa, chocolate, jars of marmalade,

cans of fish. Wigs, prayer shawls, tiny

Torahs, skullcaps, phylacteries

we carried.

Warm winter coats in the heat of summer

we carried. On our coats, our suits,

our dresses, we carried our yellow stars.

On our baggage in bold letters, our addresses,

our names we carried.

We carried our lives.

Shot (excerpt)

shot in the synagogue

shot up against the wall in the headlights

of the truck

shot in the farmyard by the dung heap

shot in the hospital, the maternity ward

shot in the city, the town, the shtetl

shot in their houses, in the streets,

in the market square

shot in the cemetery

shot in the warehouse after machine-gun muzzles

were pushed through holes in the walls

shot in the roundups trying to escape

shot in bed

shot in their cribs

shot in the air, the baby thrown over its

mother’s head

shot because they stole a potato

shot because they were betrayed for a kilo of sugar

shot because they weren’t wearing the yellow star

shot because they were wearing the yellow star

shot by the Einsatzgruppen

shot by the Reserve Battalion of the German

Order Police

shot by the Gestapo Firing Squad

shot by the Waffen SS and the Higher SS

shot by the Hiwis-Ukrainian, Latvian,

and

Lithuanian volunteers

shot by the Hungarian Fascist Nyilas,

the Arrow Cross

shot by the Polish police and Polish partisans

shot by the Croatian Ustasa

shot by the Romanian army, police, gendarmerie,

border guard, civilians, and

the Iron Guard

shot by the Wehrmacht

shot by old men in the German Home Guard

shot by young boys in the Hitler Youth

shot in Aktion after Aktion as if it was

“more or less our daily bread”

shot in the search-and-destroy mission,

the

Jew

Hunt

shot in the “harvest festival,”

the Erntefest

shot in order to make the northern Lublin district

judenrein

shot in Zhitomir, Poniatowa, Józefów,

Trawniki

shot in Lomazy, Parczew, Bialystok,

Kharkov

shot in Bialowieza, Luków, Riga, Poltava

shot in Międzyrzec, Khorol, Kremenstshug

shot in Slutsk, Bobruisk, Mogilev, Vinnitsa

shot in Odessa, Lvov, Kolmyja, Minsk, Rovno

shot in Majdanek and Brest-Litovsk

shot in Neu Sandau and Tarnopol and Rohatin

shot in Dnepropetrovsk

shot in Kovno, Pinsk, Berdichev, Tarnów

shot in Kamenets-Podolski

shot in Krakow, Szczebrzeszyn, Siauliai

shot in Stolin, Kielce, Lutsk, Serokomla

shot in Drogobych, Luga, Delatyn

shot in the Warsaw Ghetto

shot in the ravine of Babi Yar

shot in Bilgoraj, Nadvornaya, Stanislawów

shot in David Grodek, Janów Podlesia

shot near Zamosc

INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN HERZ

WTH: Can you tell our readers what first

moved you to write about the Holocaust?

SH: Many years ago after

reading Anne Frank's poignant diary I was tormented by her life and death—and I realized I was

born the same year as Anne, 1929. And I recall thinking "What was I doing knocking around high

school with a big black H on my chest that said Football,

while Anne was wearing a yellow star that said Jood and was

forced into hiding and deported to Auschwitz and to her death in

Bergen-Belsen. So I decided to write a poem on what would have been Anne's

sixty-fifth birthday—June 12, 1994. It was called You Were Fifteen

That Day. The poem ended with the lines:

You were fifteen that

day

And I, a Jew born in

America in 1929,

the same year you were

born, Anne

am in my sixty-eighth

year.

I was elated when the

poem was published. Around the same time, I started working towards my Master's degree in

English and joined a poetry writing class. One of our first assignments was to write a poem on

Thanksgiving. So, remembering as a kid hearing Hitler shouting on the Philco and my

grandfather showing me pictures of the Nazi Swastika flying from the windows of his former home in

Oppenheim, Germany, and saying "I'll never go back, that Hitler's worse than the Kaiser . . ."

So I decided to put that into my Thanksgiving poem and to show my family in conversation

at the Thanksgiving dinner table in 1938, a few weeks after the pogrom in

Germany and Austria called Kristallnacht—the night of the broken

glass—which was considered the start of what we now call the Holocaust or

Shoah. I called my poem Thanksgiving, 1938. Here's my grandfather's voice in the poem:

"What do you think

about the synagogues

burning? All those

synagogues, all those

Torahs, all that glass

breaking in the stores.

Next thing they'll be

burning Jews.

I wrote my brother:

'Ludwig, get out of

Oppenheim, get out of

Germany,

before soon you won't

anymore be able.'

So, what do you think?

asks my grandfather.

"It'll pass, I

think it'll pass,

it usually does,"

says my father.

"Do you think you can pass me some dark,

and some white?" I

ask.

A short time after I got my degree, I made a trip to Poland with a couple of my

college professors. We went through all the major killing centers—Belzec,

Chelmno, Majdanek, Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor—it was mind-boggling. On

returning, I continued researching everything I could about the Holocaust, spent

several weeks at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in DC, and also

became a sort of ersatz member of the Child Holocaust Survivors of Connecticut. Even though I felt sort of strange not being a survivor, they

welcomed me with open arms. I found a survivor who was telling her story

to mostly schools—she asked me to join her and read some of my poems—I did,

and it worked out swell—I became sort of her Greek (or Jewish)

chorus, interspersing my poems with her poignant story of survival—her name is Anita Schorr, and I wrote a poem about her—it's called MARKED—which also became the title

of my latest book of Holocaust poems. Here's the first stanza:

at nine

you wore the yellow

star,

the Star of David

that marked you Jew,

marked you for Auschwitz

where you lost your name

for a number—

71569

WTH: Has how you write about the Holocaust changed since you began

writing these poems?

SH: I'm not sure it's

changed, I would say it's grown, matured, as I became more aware of the magnitude of this bloody

slaughter. I started out with a small chapbook of Holocaust poems, then another chapbook,

then a full volume, and now an even more extensive 4th collection.

WTH: What struck us

immediately was how many of the poems seem like found poems. The

first poem in the book of course is titled "Found Poem," but many of

the poems that follow also appear to be "found," given that they are based on

statements made by Adolph Hitler, German soldiers, and survivors. Can you talk about your

process of

transforming existing materials into poems?

SH: I've been doing

this—writing these poems for so long now—I don't even think about using found

material on the Holocaust if it

helps to give some meaning to the unfolding history of this dark bloody

time—but maybe a few

of my readers' responses might answer this question better than I

can:

"I admire your

cleverness with words, lists, names . . . your focus on detail, your sense of

history, makes this material importantly new . . . it feels like history

distilled."

"You have brought

many new dimensions to a worked over subject—reworking Reich orders,

excerpting quotes from Nazi propaganda of the time, and basically anchoring

everything you write in the bitter reality of history is a brilliant stroke. Most Holocaust reflections are personal and not communal as is yours. Most do not gather up the shards of glass from Kristallnacht and surround their art with them. You do, and because of this, and because of the

voice that you adopt as a sincere and

horrified student of all the horrors, your poems stand out as a collection that

is actually designed to make the reader never forget."

WTH: Please

tell us about your decision to apparently remove yourself from so many of the

poems.

SH: Sorry, I really can't

answer this question—I wasn't conscious that I was removing myself from my

poems. Take, for example, a poem I wrote on looking at a picture of

children on the eve of their deportation from Westerbork in

Holland. Here are some of the final stanzas from that poem:

And then it hits you

that this

Westerbork is the same

place where

Anne Frank and her

family would

leave in the last

transport

for Auschwitz, leave

only months

after the children in

this picture

were deported. Was there

a similar

picture somewhere of

Anne Frank?

Look: in the back row,

that chubby

boy in the sailor suit

is pulling

his mouth apart, hamming

it up:

a class clown just like

you were

back in 1944, the year

this picture

was taken, the year you

graduated

from Ravinia Grammar

School,

the year you remember

thinking

Hitler and Goering were

some kind of

comedy act, like Abbot

and Costello.

WTH: For us, one of the

remarkable things about your book is that it is not only a book of poetry, it

is also a historical document, even a history perhaps. We can see teachers

using it as the initial text in a course on the Holocaust itself or on

Holocaust literature. Was this your intention?

SH: Thanks, you're right on

here. A short time after I got my degree, I made a trip to Poland with a couple of my college professors. We went through all the major killing centers—Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor—it was mind-boggling. On returning, I continued researching everything I could about the Holocaust, spent several weeks at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in DC, and also became a sort of ersatz member of the Child Holocaust Survivors of Connecticut. Even though I felt sort of strange not being a survivor, they welcomed me with open arms. I found a survivor who was telling her story to mostly schools—she asked me to join her and read some of my poems—I did, and it worked out swell—I became sort of her Greek (or Jewish) chorus, interspersing my poems with her poignant story of survival—her name is Anita Schorr, and I wrote a poem about her—it's called MARKED—which also became the title of my latest book of Holocaust poems. Here's the first stanza:

at nine

you wore the yellow star,

the Star of David

that marked you Jew,

marked you for Auschwitz

where you lost your name

for a number—

71569

WTH: Has how you write about the Holocaust changed since you began writing these poems?

SH: I'm not sure it's changed, I would say it's grown, matured, as I became more aware of the magnitude of this bloody slaughter. I started out with a small chapbook of Holocaust poems, then another chapbook, then a full volume, and now an even more extensive 4th collection.

WTH: And a related question: Whom do you see as

the audience for your book?

SH: Hmm, I haven't thought

about that—I guess I would say everyone and everybody, with a special

emphasis on making these poems available to the younger generation.

WTH: Can you tell us about the writers who have

influenced you, especially in regard to your use of poetry as history, and

history as poetry?

SH: I was asked a similar

question not too long ago that appeared in a book called Poets Bookshelf

II: Contemporary Poets on Books That Shaped Their Art. Here's what I said:

Walt Whitman, Leaves

of Grass

Allen Ginsberg Howl (also

"Kaddish")

Mary Oliver, New

and Selected Poems

Gary Snyder, Turtle

Island

Primo Levi, Survival

in Auschwitz

Anne Frank, The

Diary of a Young Girl

Art Spiegelman, Maus

Martin Gilbert, The

Holocaust

Looking up at my

bookshelf at shelf after shelf of books on the Holocaust, I find it hard to make

a list—but I suppose if I were to pick just one, it would be Primo Levi's Survival

in Auschwitz, which is for me a remarkable, moving and memorable prose poem.

But how can I leave out

William Carlos Williams, Richard Hugo, Donald Hall, Philip Levine, Yusef

Komunyakaa, Gerald Stern, Mark Doty, Thomas Lux, Galway Kinnel, Pablo Neruda,

Yehuda Amichai, Stanley Kunitz, Hayden Carruth. etc, etc.?

WTH: Besides visiting the camps and killing centers and

interviewing survivors (and even a former Nazi boy soldier) . . . before

immersing yourself in the extensive literature and history and poetry

of the Shoah, is there anything

else that you can think of that influenced you as you wrote your

poems?

SH: Yes, one thing I still

keep going back to again and again, and that's Claude

Lanzmann's powerful 9½ hour documentary film Shoah. Instead

of all those pictures of piles of bodies and historical

footage, what Lanzmann gave me (or, I should say gives us) is a

profound, moving, and insightful look into the mind-set of so

many of the killers, victims, and even the bystanders—and he does

so by visiting the crime scenes.

WTH: You have two very very

long, one might call List Poems, "Shot" and "The Shooting

Never Stops." Each line in these poems starts with the word

"Shot." What can you tell us about these poems?

SH: Well, first of all I

would like to quote a few eye-opening words by the writer David Denby

who recently said: "Roughly as many

Jews were killed by bullets as gas in the Holocaust,

a fact not widely known to this day."

So, there's nothing much

to tell you—but I can, I hope, show you in these long poems some of the many

many shots from the killers. Here's a small example:

shot in bed

shot in their cribs

shot in the air, the

baby thrown over its

mother's head

shot because they stole

a potato

shot because they were

betrayed for a kilo of sugar

shot because they

weren't wearing the yellow star

shot because they were

wearing the yellow star

I would also like to

mention how these "Shot" poems have made an indelible impression on

several classes of students in the Middle Schools—for example, kids would

stand in a long long line, each with a big sign in bold letters that said

SHOT—then each of them would take a turn and read a line from the

Shot poem and flip their sign down

shot after their eyes

were gouged out because they

refused to undress

(shot sign is flipped

down)

shot after being driven

into the grave and made to

lie down on top of those who had been

shot before them"

(shot sign is flipped

down)

And so, on and on down

the long line of students being, one might say, felled by the shots.

It was very

startling and moving, to say the least.

__________________________________________

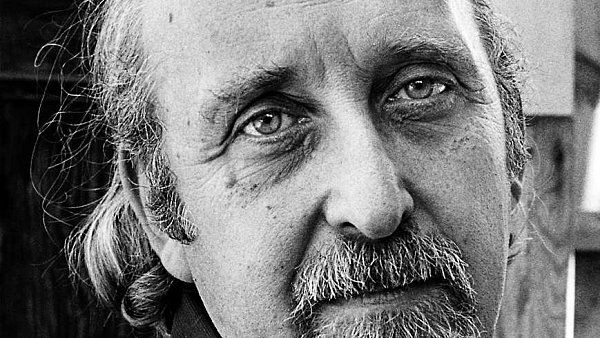

Stephen Herz's poems have been widely

published. He's a winner of the New England Poet's Daniel Varoujan Prize. This

collection—Marked—is the culmination of two chapbooks, a volume of

poems—Whatever You Can Carry—and many new poems that cover the years of this

dark, bloody time of death and destruction and evil we call the Holocaust or

Shoah. Several schools and universities have adopted Herz's poems as part of

their Holocaust studies curricula. Mr. Herz lives in Westport, CT and New York

City.